Private investigator of Solar System bodies from California

Imagine how many other discoveries, that we’re yet to uncover, exist in data taken in surveys 10-20 years ago, because no one’s looked at it.

Sam Deen

As a child, he began searching for exoplanets, but soon he was not satisfied with simply clicking on the offered images. He wanted more, to use the available data for his own scientific research. After a year, he left university studies to devote all his time to astronomy. He finds lost asteroids, comets or identifies small bodies of the Solar System overlooked by scientists, starting from new near-Earth asteroids, unknown moons of Jupiter, and ending with extremely distant trans-Neptunian objects. Self-taught, who has developed into a unique expert, the detective of the astronomical archives, Sam Deen.

First, introduce yourself to us.

Well first off, I'm a 23 year old amateur who is not currently employed or a student. I did go to Northern Arizona University for a year, but I didn't find university a very good fit for me. At least I've got plenty of free time to do astronomy!

When you became interested in astronomy and why?

I've always been rather interested in space, but that interest really took off when I was 10 or 11; I learned in a magazine about the Planet Hunters citizen science project, where you could go through Kepler telescope data and hunt for exoplanets nobody had seen before.

What attracted you to that project?

The idea was incredible to me- that I, a pre-teen with no degrees or field experience, could actually do real astronomical research. Over the next few years, I got more involved in the citizen science community, trying to learn everything I could about the universe and see how many ways I could best contribute to astronomy. Anyway, starting off seeing how much we're still learning about the universe really helped inspire me to learn as much as I could and see how I could help out.

At the time (around 2011) the field of exoplanet study was super young; I was reading all the time about new exoplanet discoveries in distant systems with all sorts of weird details. Planets orbiting pulsars, giant planets being evaporated, hints of planets around some of the very closest stars to the Sun... I wanted to be able to help with that, to maybe find some extremely strange planet that nobody had noticed before and stump astronomers. When I saw the advertisement for the project, it almost seemed made for me personally.

As a child, you fell completely into astronomy. Did you consider becoming a professional astronomer?

If you asked me ten years ago, I would have said being a professional is my goal, and it still is to a degree, but over the years I've taken a liking to being a researching amateur. If I became a professional, I would only be doing the same job I'm already doing, but with several years of university work in the way. For the time being, I'll proudly call myself an amateur.

Where did you get your information about space? Was it the internet or books? Do you remember your first astronomy book?

My memory is a bit hazy on this, but I do remember obsessively reading through the Eyewitness Books series on space & astronomy. At one point I managed to pester my parents to buy me a big solar system reference book published by NASA in the 80s or 90s, which had detailed pictures and details of everything in the Solar System we'd visited by that point. I remember Mercury was still half-blank because only Mariner 10 had been there when the book was published, and Pluto was entirely blank! Not even that Hubble image to work with. That's probably my favorite astronomy book, both because of how much it beautifully illustrated & explained about the Solar System, and because of how much it didn't. It really showed how much new we had learned about space in just the last 20 years, and how much we were still learning.

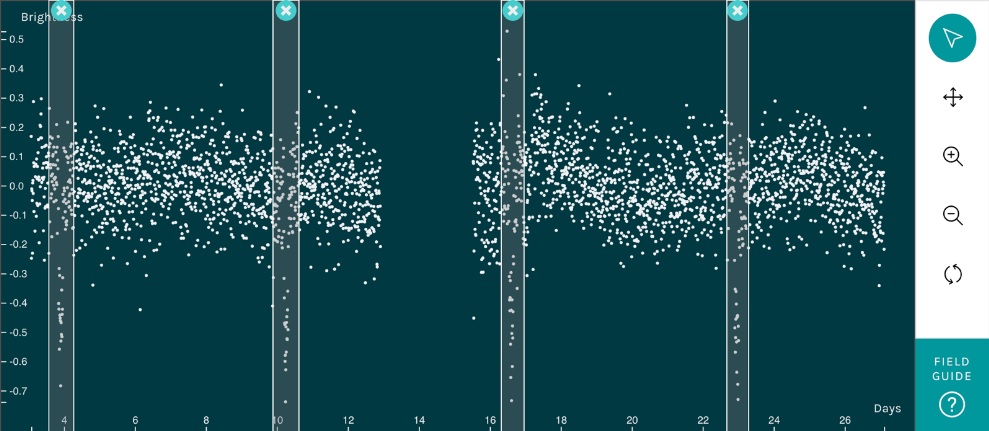

Let's go back to the Planet Hunters project. The Kepler spacecraft monitored around 150,000 stars and their changes in brightness. They then looked for candidates for exoplanets from the light curves. Evaluation software is not perfect, and the human eye will pick up changes in brightness that the software misses. And this is where volunteers came into the scene. They examined light curves and reported. Can you describe how your hunt for exoplanets took place?

Early on for me, it was just browsing the individual data images on planet hunters for zooniverse, though more recently (in my searches over the last several years) it's a bit more involved - I have been searching especially nearby stars to the Sun in TESS spacecraft data, using software like Allan R Schmitt's LCTools and the AAVSO's VStar, all to search for dips and unusual features in the stars' light curves. At one point I thought I had discovered an exocomet transit around one nearby star system, and had almost finished writing a paper on it, before doing a final review of the data and discovering it was a processing error...

When I opened the Zooniverse website, I found 30 space-related projects. I'm assuming you didn't just stop looking for exoplanets. Which project was next?

The first Zooniverse project I ever joined was Planet Hunters- it's the origin of my interest in exoplanets as well as my name around the internet (planetaryscience). I ended up spreading out quickly to work on many other projects quite a bit though! After a few months of planet hunting I started searching for more Zooniverse projects to take part in, and tried at least a dozen or more, but in the end Galaxy Zoo grabbed my attention best. It was the oldest Zooniverse project, and had the hugest community. The thing that kept me most interested wasn't so much the galaxy classification work itself, but more the sheer amount of undiscovered data there was in the project's source survey. I would often spot rogue asteroids and supernovae near the galaxies, which usually turned out to be unknown. The community there was very tolerating of my largely stupid and off-topic questions, which only made my fascination with these things even greater.

More than 10 years have passed since then. Are you still working on Zooniverse projects today?

I don't work on Zooniverse projects quite as much as I used to, though I still come back occasionally. Sadly while Zooniverse projects are an excellent way for amateurs to contribute to science, there's often not much way for you to do your own research and study with the data. Hunting for lost asteroids could never work on the website, for instance. The average internet user just wouldn't be able to know how to do it.

While working on classification of galaxies, the inspiration came for your own research. You started using publicly available archives of world observatories. Which one was the starter?

For the longest time I only used Sloan Digital Sky Survey / SDSS data. It was what Galaxy Zoo worked with, and was very easy to look into. The survey took five exposures in different color filters that made moving asteroids appear as a line of colored dots- very easy to see against the background stars and galaxies. For a long while I was hesitant to use anything else due to how complicated most other surveys seemed at the time, but eventually more and more new archives popped up, and I gave in.

Astrometry is a branch of astronomy focused on determining the exact positions of celestial bodies. Their orbits are counted from them. The more observations we have of a given body, the more precisely we can determine the position of the object in the future. You realized that the archival data offered valuable information about asteroids, even though they were originally acquired for completely different purposes. Was it an easy and direct path from the Galaxy Zoo project to asteroid astrometry?

Yes and no- "easy to learn, yet difficult to master" isn't usually a term you would think of scientific fields, but I think it definitely applies to asteroid hunting. My very first bits of work with asteroid hunting were deceptively easy, just clicking on images and reporting where it said the asteroid was. My measurements weren't very good back then. It took quite a bit of trial and error to learn how to get the right positions and times, and even longer to learn how to do it quickly. I spent a couple years being a complete newbie at asteroid hunting- I would say it wasn't until 2021 that I started to feel like I knew what I was doing!

When did you switch from simply measuring positions of moving bodies to more demanding work?

It's difficult to give an exact moment to this - soon after beginning my asteroid observation work I realized that my observations were more useful for some objects than others, but also usually harder for those objects. Making another observation of Ceres helped astronomers a lot less than finding more observations of a distant Kuiper Belt object not seen since the 2000s... It was a bit of a slippery slope going from measuring well-known asteroids to adding a 4th year onto 3-year-arc asteroids, to outright measuring asteroids without any known orbit at all.

You are self-taught, but you obviously couldn't do without the help of others, more experienced. Who did you turn to with your questions?

The Minor Planet Center's own staff have been very helpful in dealing with my often inane questions and confusions. Many of the folks at the Minor Planet Mailing List have also helped give me reality checks and advice on many of my earlier, usually sillier ideas.

Who gave you the most advices?

I think the single most helpful source would have to be Carlos & Raul de la Fuente Marcos - I first contacted them in 2015 after confirming the Uranus co-orbital 2015 DB216. They had written a paper on it, and I was impressed that my asteroid hunting work could be helpful enough to cause a paper to be written! We came into regular contact then, and have collaborated on several research topics from other stars approaching the Sun to the poorly understood population of Atira asteroids, asteroids whose orbits are entirely inside of Earth's. They have been invaluable in helping introduce me to the more professional sides of astronomy research.

Do you have some hero astronomers - people you admire and are inspirations for you?

A huge inspiration to me has been Mike Brown, the discoverer of most of the Solar System's dwarf planets. His work in discovering the Kuiper Belt and the proposal of Planet Nine has hugely inspired me to go searching the outer Solar System for minor planets and completing our picture of the Kuiper Belt and beyond.

Which archives do you usually use for astrometry work?

Anything I can get my hands on, really - NOIRlab has data from Kitt Peak and Cerro Tololo, IRSA has data from the WISE spacecraft and Zwicky/Palomar Transient Facility, and STScI has PANSTARRS. No one survey will be a perfect source for data, so my best asset in astrometry is having as many diverse sources as possible to pull from.

Which is your favourite data source and why?

It's difficult to say, as different sources work best for different purposes, but if I had to pick it would have to be DECam. Although it only images most of the sky a few times of year, it observes the sky deep enough to see nearly every asteroid other surveys have found, even those beyond Neptune. If DECam didn't exist, we would probably be years in the past on research & discovery in the distant solar system.

And what programs do you use for asteroids identifications and orbit calculations?

I mainly use find_orb, a very excellent program created by Bill Gray for orbit calculation; I wouldn't be anywhere near where I am now if not for that program. Its features and abilities are too many to list, but anyone wishing to learn more should check out projectpluto.com.

How much time do you spend per day browsing the archives?

It varies a lot, being still just a hobby of mine. I will sometimes go weeks without checking a single image, and occasionally up to 12 hours a day going through a series of recent or interesting discoveries. On average, I imagine it is probably about 2-3 hours each day looking for observations.

How do you choose the objects you go to explore?

It's really up to my whims of the day - sometimes it will be centaurs/trans-neptunian objects only observed for a few days, or short-period comets we haven't seen in years. Once in a while, I'll even go looking through bright unidentified objects surveys found to see if anything unusual pops up. That last method is how I helped discover comet P/2020 A4 (PANSTARRS-Lemmon).

So you have discovered a new comet! Tell us how it happened. Don't you regret that the comet, despite the fact that it would never have been known without your efforts, bears the designation P/2020 A4 (PANSTARRS-Lemmon)?

One of the biggest attractions for me in my archival research is finding the things that were overlooked, and one way I've done that is with the Isolated Tracklet File- I don't recall if I explained this before, but in case I didn't, it's a sort of garbage bin of observations of moving objects that the minor planet center hasn't been able to link to any known asteroid; there's a lot of everything in there, unstudied and unknown.

At that time, I was looking through the file for unusually bright objects that couldn't be identified, and I came upon an object observed by the Mount Lemmon Survey from February 2020 that was around magnitude 19.5. Considering that nowadays 22nd magnitude asteroid isn't so unusual to discover with all the huge survey telescopes operating, something this bright, in the northern hemisphere, moving no different to a normal asteroid belt object...

It piqued my curiosity. I found some ZTF mages that confirmed it was indeed a real object, and as I made more measurements, the more increasingly obvious it became that this wasn't a typical asteroid belt object. It seems this short-period comet had been cruising through the asteroid belt relatively peacefully, but in early February had a sudden outburst that brought it to magnitude 19, before quickly returning back to its typical 21-22. It's a bit of a shame that my only credit for the comet is informal, but PANSTARRS and Lemmon do deserve at least as much credit as I do: if the latter had not made those observations in February, I never would have known of the comet's existence, let alone be able to publish that.

Ultimately, I'm just glad that I could pry a nearly-missed comet out of obscurity, and increase our knowledge of the solar system a little more, where nobody else would have (at least not for quite a few more years). That's reward enough for me any day.

I know only one other amateur comet discovery from the archives, of course not including the SOHO comets. Perhaps it is time to reconsider the comet naming rules. If amateurs did not devote themselves to exploring the archives, we would be deprived of such discoveries. For them, it would be a moral award and a motivation for others to become more dedicated to researching archives and finding objects that professionals have overlooked. I suppose if the name of the comet was P/2020 A4 (PANSTARRS-Lemmon-Deen) you wouldn't mind...

I don't think I'd mind myself, and I could certainly see it motivating more pragmatic researchers.

Describe your search process for us.

After I've found an asteroid I want to search for, usually the first step is figuring out what I expect to find. For a bright near-earth asteroid, I'd probably go searching for a frequent but shallow survey like the Zwicky Transient Facility, but for a very dim and distant object I'd look instead for less frequent, much deeper sources like DECam or the Subaru telescope. At that point, it's mostly a game of putting the object into one of the many surveys' image searches and balancing which image has the best chance of spotting the asteroid with which image is going to most improve the asteroid's orbit. If an asteroid's position is only uncertain by a fraction of an arcsecond, it's probably not going to help improve the orbit that much, but if it's uncertain by thousands I don't have much chance of finding it at all. Even still, that might be worth the effort for a truly exceptional asteroid.

What does your normal working day look like?

A whole lot of picking a group of asteroids to go through, finding a third of them with no trouble, trying not to be bothered that a third are completely unfindable, and then spending the rest of the day hunting down the last third. (Spoiler alert: You can't recover all of them!)

What do you see as the greatest benefit of searching archival images?

Nearly all of the discoveries we've ever made in space, from the many moons of Jupiter and Saturn, to the many galaxies in the very early universe, have existed for all of human history in almost exactly their current state. The only limits to what we've found have been our telescopes, and the people looking through those telescopes. While new, large telescopes are expensive and difficult to build and maintain, nowadays looking through that data is basically free. We get a second chance to look through the solar system in hindsight, finding objects we know of now, that would have been groundbreaking when they first appeared in old data. Furthermore, with current discoveries it's usually difficult to say if we would have found an object 'anyway' - if PANSTARRS hadn't discovered 1I/ ʻOumuamua, who's to say another survey wouldn't? In archival work, we can truly say that ONLY searching archival data could have found the object: it WASN'T discovered by anyone back then! What better proof of worth can you ask for?

What do you consider your most valuable achievement?

At the moment, I'm most satisfied hunting down the extreme trans-neptunian object (ETNO) 2003 SS422. It's hardly the most unusual distant asteroid astronomers have found, but from my early years of asteroid hunting I'd tried to recover it, as the only lost ETNO. I remember trying at least once a year with new searching techniques I'd learned each time, but always eventually ending in failure. When I finally managed to spot it in 2021, it felt like I had truly graduated to being an expert in archival asteroid searching. I think I'd put at least 100 hours of work into just finding that thing!

Do you know of other amateurs who are dedicated to such astrometry work?

A friend of mine, Kai Ly, is another excellent one. We've worked together on finding and recovering several lost moons of Jupiter, as well as improving the orbits of some very distant objects. A good few others have also gotten into the field in the last year or so; if that's anything to go by, we'll probably have dozens of people doing archival astrometry in a few years from now!

What advice would you give to interested amateurs who would also like to do astrometry?

I'd suggest just joining communities of people who support amateur research like this - the Minor Planet Mailing List, a local astronomy group, or citizen science projects like zooniverse. As long as you're not afraid of asking questions and getting in contact with people, you're bound to start contributing to the field fast.

Two total solar eclipses could have been seen from the USA lately, one in 2017 and the second a few days ago. Have you seen this extraordinary phenomenon?

I've traveled to see both eclipses (from Idaho and Ohio respectively), and they were both spectacular on a level that few other natural phenomena are. It's one of those things that everyone deserves to see at least once in their life... many astronomical events are overblown in the media, setting people up for disappointment, but absolutely not this one. I hope to see another one before the end of the decade, but I'm not quite sure where yet.

You are searching data from the world's largest observatories. Have you visited any of them?

I've been to a fair few over the years: Mount Palomar in California, where the Samuel Oschin Telescope sits (currently being used for the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF), arguably the most prolific survey currently going on in the sky with an image of nearly the whole northern sky every few nights) though this visit was before I knew any of that. I also spent a year at Northern Arizona University, within walking distance of Lowell Observatory, so I managed to steal quite a few trips over there. Finally, I went on a tour up to the Mauna Kea Observatories a few Junes ago; the observatories (as well as the mountain) were certainly the most breathtaking of any I'd been to, and I hoped the skies would prove equally breathtaking overnight, but apparently that June had other plans, because it ended up blizzarding on the summit that night, all night; the tour group gave us all a refund, in what they said was the very first time in their 20+ year operation history. Just my luck!

Many amateurs are tempted to see with their own eyes the space objects that we admire in photographs from telescopes or space probes. Do you have your own telescope and do you observe sometimes?

I've got a 6" aperture scope at home that I break out for comets or other astronomical events, but unfortunately light pollution has gotten much worse where I live (the suburbs of Los Angeles) over the years, and on some nights it's only able to reach a little fainter than the naked eye in a light-unpolluted sky...

Spending hours in front of your computer can be exhausting. What do you do in your free time, away from your PC?

To be honest, I spend a lot less time away from my computer than I ought to... While searching the archives, I lose track of time. I've been hoping to work my way to an astronomy-related job for a while now, but for the moment I have had no such luck. So, when I need a rest, I do gardening, hiking, the occasional travel when I'm able, but most of my hobbies are here: music making, occasional writing, and improving Wikipedia on astronomy topics.

New sky surveys like Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST) and Thirty Meter Telescope will be added in a near future. Are you looking forward to the data from their observations?

Absolutely. The Zwicky Transient Facility at Palomar Observatory, California has been working as a 'lite' version of LSST for a few years now (surveying the whole visible sky every few days, quick asteroid searching, but much smaller telescope than VRO's) and it's been incredible at discovering near-earth objects and bright asteroids. LSST publishing their data just a day after creating it will be a huge milestone in astronomy data availability, and goes to show just how valuable archival data is becoming.